About CIM417 Creative Practice Research

Chia-yu Chang's Artist Statement

Artist Statement

I create through animation, character design, and art as a way to share what I find interesting in my mind. For me, making is about fun, curiosity, and discovery, and I enjoy trying new things rather than following strict rules.

My work often draws inspiration from sweet and beautiful imagery, as well as from memory, environment, and technology. I’m also excited by learning new tools and experimenting with different approaches, which helps me grow my own style.

In the end, I want my art to invite others into the playful and imaginative worlds I enjoy building.

"Fashioning Professionals: Identity and Represention at Work in the Creative Industries" this book's main idea is that "to be a progessional is not only to do a particularkind of work, but to fashion a particular kind of self" (p.2).

It has tree Chapter, and I going to write small summary to each.

Chapter one: Inventing

The first part, “Inventing,” discusses how new roles in the creative industries are being created in response to media and technology changes. The editors note that “new identities are being invented in response to changing technologies and economies” (p. 27).

Chapter two: Negotiating

In the chapter about Leonor Fini, Kollnitz writes that Fini “transformed her self into an art-work” (p. 139). She performed her identity through costume, image, and persona.

I like this idea because it reminds me that art can include not just what you create, but how you present yourself. Fini used her appearance and actions as part of her creative language.

When I share my animation or character design, I am also showing something about myself — my sense of beauty, mood, and imagination.

Chapter three: Making

The final section, “Making,” focuses on the relationship between craft, technology, and creative identity. Rossi describes the modern maker as “a hybrid figure, working between digital and physical production” (p. 215).

This connects strongly to my own process. I like to try new tools and technologies in my projects. Every time I learn a new software or experiment with a technique, I feel like I am shaping my identity as a “maker.”

The book says “making is a way of knowing and a way of becoming professional” (p. 218). I think this means that through practice, we not only gain skill but also discover who we are as artists.

For me, this book mainly helps me understand that being a creative professional is really about continuous self-fashioning. It’s not something that happens once — it’s an ongoing process of shaping who I am through what I create and how I work.

From reading the chapters, I feel that a creative professional needs to:

-

stay curious and keep exploring,

-

develop their own art style or way of seeing the world,

-

and be willing to try new tools and technologies.

Another point I realise is the importance of recording my creation process. This would help me look back and see how I grow. Honestly, I don’t update my process very often — partly because I feel lazy, and partly because I never know what to write. If I write too little, it feels strange, but if I write too much, it takes a long time to read. But after this reading, I understand that documenting the process is also part of forming my professional identity.

APA7 Reference:

-

Armstrong, L., & McDowell, F. (Eds.). (2018). Introduction. In Fashioning professionals: Identity and representation at work in the creative industries. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Week 2

Write an annotated bibliography that you can add to throughout your studies.

An annotated bibliography is like a bibliography with a written summary of each source. Here are some examples.

Find three articles or chapters related to your practice,

Copy or write a reference for each one in APA style,

Under each reference, summarise what is in the article or chapter and how it is relevant to you.

Book Van

-

Annotation

Aylinn Nguyen is an aspiring environment artist currently studying at Think Tank Training Centre. She loves to create and learn, and she hopes her work can inspire others.

The source explains why and how she created her 3D model “Book Van.”

She made this 3D model because she discovered the concept art for the Book Van by Star CG on ArtStation. This inspired her, and she thought it would be a great opportunity to learn how to translate a 2D concept into 3D. She succeeded, and through the project she learned new skills such as prop workflows, animation, and lighting.

-

Reflections on article

I like her passion and the way she becomes inspired through her process. I chose this source because I noticed that we have a similar way of getting inspiration, and her work was successful. When I saw the “Book Van,” it made me think, “Wow, that’s so cute!” I also got some ideas from this piece.

Reference List

-

Nguyen, A. (2022). The Gallery: The Rookies. 3D World, 2023, Issue 300 , 20–21. URL: https://flipster.ebsco.com/zh-TW/c/gemy63/reader/3612372?callbackUrl=https%3A%2F%2Fflipster.ebsco.com%2Fzh-TW%2Fc%2Fgemy63%2Fdetails%2F4030509%3FbackTo%3D%252Fc%252Fgemy63%252Fbrowse&accessionNumber=3612372&pageSet=10&page=0

Diving into Pandora's Magic. Animation

-

Annotation

Trevor Hogg explains how director James Cameron and his VFX team created the stunning visual effects in Avatar: The Way of Water. The article discusses where their ideas came from and the challenges they faced during production.

-

Reflections on article

Avatar: The Way of Water amazed me with its colors, patterns, variety, and use of shape language—for example, the Wood Sprites, which are jellyfish-like, inspired by shallow water marine life. When I first saw this movie, the depiction of the ocean was incredible and left a strong impression on me.

Director James Cameron and his VFX team emphasize that their approach to visual effects is the heart and soul of creating Avatar’s world and its otherworldly characters. Audiences can feel the care and attention that went into these details.

The parts that surprised me the most were:

-

The Weta FX team created 57 new ocean creatures for the film.

-

They developed complex simulations for water interactions, including how water drains from hair, sheds off skin, how a person emerges from water, how costumes carry and release the water’s weight, and how water itself reacts as it is displaced around the body. This proved to be a very challenging and technically demanding task.

This inspires me to think about how water, movement, and physics can influence my animation work

Reference List

-

Hogg, T. (Feb, 2023). Diving into Pandora's Magic. Animation, Feb 2023, Issue 2 Volume 37, Pag:52-54. URL: https://flipster.ebsco.com/zh-TW/c/gemy63/reader/3536996?callbackUrl=https%3A%2F%2Fflipster.ebsco.com%2Fzh-TW%2Fc%2Fgemy63%2Fdetails%2F4357792%3FbackTo%3D%252Fc%252Fgemy63%252Fbrowse&accessionNumber=3536996&pageSet=28&page=0

HOW CAN I CREATE A REALISTIC CRYSTAL MATERIAL?

-

AnnotationThis is teach how to use the Blender to create a realistic crystal material by Pietro Chiovaro. And has note that this material can work with both the Cycles and EEVEE render engines in Blender. But he highly suggest using Cycles to get better reflections, shadows, and esecially lith transmission inside the crystal.

-

Reflections on articleWell, to see image that show up as know that this realistic crystal material is so good and bueatful. I could apply these techniques in my 2D-to-3D animation workflow to add realistic props or effects. And I have ideas that could it can make gradient colors or add some mysterious patterns.Last thing is I very agree that use Cycles render engines in Blender, but that will take long time than EEVEE render. Other issuse is my laptop may not handle the long render times.

Reference List

-

Chiovaro, P. (N.D). HOW CAN I CREATE A REALISTIC CRYSTAL MATERIAL?. 3D World, May 2024, Issue 311, Pag:80. URL: https://flipster.ebsco.com/zh-TW/c/gemy63/reader/3865686?callbackUrl=https%3A%2F%2Fflipster.ebsco.com%2Fzh-TW%2Fc%2Fgemy63%2Fdetails%2F4030509%3FbackTo%3D%252Fc%252Fgemy63%252Fbrowse&accessionNumber=3865686&pageSet=40&page=0&auth-callid=16360524-7160-4e6d-9997-f72ff1f99e7c

Week 3

Reading 1

A Question of Genre: de-mystifying the exegesis | Published in TEXT

Brady uses the bowerbird motif to describe her research process: she collects “blue things” from many fields (history, cartography, archaeology) in a way that seems random, but actually helps her creatively (Brady, 2000). This descriptive metaphor shows how creative practitioners gather research from different, seemingly unrelated areas to build a richer creative work.

Two parts of the creative process Brady identifies are:

-

Knowledge Gathering: Brady describes gathering “working knowledge” across many disciplines—not specializing in any one, but developing enough to pick the “blue pieces” that matter (Brady, 2000).

-

Reflective Creative/Academic Synthesis: She notes how her creative writing and exegesis (academic writing) intertwine: “the academic became the creative; the creative became the academic” (Brady, 2000).

I think Brady’s metaphor of the bowerbird is powerful: it reflects a very creative research style—one that is not purely academic, but deeply imaginative. Her idea that the creative work and the exegesis can grow from the same research process is very helpful for anyone doing practice-led or creative-research projects. It shows that research doesn’t have to be rigid or formulaic—it can be playful, selective, and deeply personal, while still being meaningful and rigorous.

APA 7 Reference

-

Brady, T. (2000). A question of genre: De-mystifying the exegesis. TEXT, 4(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.52086/001c.35896

Reading 2 : Kurt Vonnegut on the 8 "shapes" of stories - Big Think

The Hero’s Journey (monomyth) is very entrenched in storytelling culture, especially in Western media, movies, and literature. Because so many writers, teachers, screenwriters, and storytellers learn it, they continue using it—it has become a “default” structure. People feel comfortable with its rising-action → crisis → resolution pattern because it mirrors many traditional myths and archetypes.

It Aligns with Human Psychological Experience

The monomyth resonates because it reflects how people often understand their own lives: a call to adventure, challenges, transformation, and return. This mirrors the “shapes” that audiences emotionally expect in narratives (Johnson, 2022). Stories built on this structure tap into deep psychological needs—growth, struggle, and overcoming obstacles—which makes it emotionally satisfying.

It’s Very Useful for Commercial Media

In film, novels, games, and mainstream storytelling—especially in Hollywood—the Hero’s Journey is practical. It gives creators a clear, marketable structure. Writers, producers, and directors use it because it reliably engages audiences and builds tension. It is also taught widely in writing schools and creative programs, reinforcing its dominance.

I think the monomyth persists because it offers a familiar, emotionally resonant structure that is easy to teach and apply in many storytelling contexts. It reflects common human experiences—such as facing challenges, undergoing transformation, and returning changed—which makes it emotionally satisfying and deeply embedded in cultural narratives. Moreover, the entertainment industry relies on its clear structure to create compelling, commercially viable stories. In contrast, Vonnegut’s “shapes of stories” model, as explained by Johnson (2022), presents a more flexible, abstract way to think about narrative that emphasizes the rise and fall of fortune rather than rigid plot points (Johnson, 2022). Although Vonnegut’s model provides a philosophically richer and more realistic alternative, many writers and creators default to the monomyth because its structure is so deeply ingrained and practical.

APA 7 Reference

-

Johnson, S. (2022, June). Kurt Vonnegut on the 8 “shapes” of stories. Big Think. https://bigthink.com/high-culture/vonnegut-shapes/

Here's a descriptive-prose:

She lived with a quiet fear that clung to her ribs like a shadow — the fear of death, of disappearing one day without understanding what life was supposed to mean. On the outside, she looked normal enough. She laughed when people expected her to laugh. She walked through the world wearing a carefully-painted smile, neat and uncracked.

But when the door closed behind her, the mask slipped.

In the dimness of her room, she curled beneath her blankets, small as a breathing question mark. The silence around her made her chest tighten. She felt powerless, lost, as if each day slid past without leaving colour behind.

Yet one thing still reached her — beauty.

Art, colour, and the soft glow of fantasy could still touch her heart when nothing else could. Sometimes a bright pink sunrise spilling over the window reminded her that something beautiful could exist even when she couldn’t feel it inside herself. Sometimes a piece of blue light drifting across a screen made her whisper, I'm alive… still alive.

This piece uses Pinterest references to create an image remix.

Note: The images may show different characters, but they are all meant to represent the same person.

Week 4

Befor do the reflection, we need to know about new terms

Research What it means: A structured and intentional process of asking questions, exploring ideas, gathering information, and making something new. In creative practice: Research includes sketching, experimenting, testing materials, doing visual studies, analysing artworks, reading theory, and reflecting on your process. It is not only academic reading — making is also research.

Knowledge What it means: Information, understanding, or skills you gain through experience, study, or practice. In creative practice: There are different kinds of knowledge: Tacit knowledge – things you know through doing (e.g., “I can feel when a design balance is right”). Embodied knowledge – knowledge in the body (drawing skills, animation timing). Theoretical knowledge – ideas from books, journals, and academic sources. Contextual knowledge – understanding your creative field, audiences, culture, trends.

Methodology What it means: Your overall approach to research — the system or logic behind how you do things. In creative practice: A methodology is like your creative strategy. Examples: practice-led research autoethnography reflective practice visual research phenomenology creative experimentation It explains why you choose certain methods and how they help answer your research question. Method = what you do. What Method means: The specific tools or techniques you use in your research. Methodology = why you do it that way.

Epistemology What it means: A theory of knowledge — how we know what we know. It asks: How is knowledge created? What counts as “valid” knowledge? Can creative work produce knowledge? In creative practice research: Epistemology helps justify why making art is a way of thinking. It explains how creative work can generate knowledge (emotional, sensory, conceptual, cultural).

Ontology What it means: The study of being or existence — “What is real?” In creative practice: This is about understanding: What is an artwork? What is a creative practice? What does it mean to “be” an artist?

Reflection part:

This week helped me understand Creative Practice Research (CPR) as a way of creating knowledge through artistic making. As an animator, this perspective feels natural, because animation itself involves constant experimentation with movement, emotion, colour, and visual storytelling. CPR recognises this kind of embodied and experiential knowledge, where creative work and research can happen together (Candy, 2006).Before this week, I mostly thought of “research” as reading articles or collecting information. Now I realise that my creative tests — such as animation drafts, colour exploration, timing experiments, or character sketches — can also function as research. These processes help me discover what works, what communicates emotion, and how my artistic choices shape meaning. Smith and Dean (2009) describe this as a cycle where practice informs research, and research informs practice, which fits closely with how I animate.Learning the distinction between methods and methodology was also helpful. My methods might include drawing storyboards, experimenting with lighting, collecting references, or adjusting movement timing. Methodology is the reasoning behind those choices — why I am experimenting in a certain direction, and how these decisions help answer my creative or conceptual questions (Gray & Malins, 2004). Seeing my process this way makes my animation practice feel more intentional and analytical.The concept of epistemology — how knowledge is produced — also connects strongly to animation. Much of what I learn through animation cannot be expressed in words alone: things like flow, rhythm, atmosphere, and visual emotion. CPR values this kind of tacit and sensory knowledge, acknowledging that creative practice can produce insights that traditional research cannot (Candy, 2006).Overall, CPR helps me view animation not only as making something visually appealing, but as a reflective and investigative process. It encourages me to document my decisions, understand my influences, and recognise that my creative experimentation is also a form of meaningful research. For me as an animator, creativity becomes both the method and the knowledge.

APA 7 reference:

-

Candy, L. (2006). Practice-based research: A guide. Creativity & Cognition Studios. https://www.creativityandcognition.com/resources

-

Gray, C., & Malins, J. (2004). Visualizing research: A guide to the research process in art and design. Routledge.

-

Smith, H., & Dean, R. T. (Eds.). (2009). Practice-led research, research-led practice in the creative arts. Edinburgh University Press.

Week 5

In this week's webinar we will consider how the creatives and the exegetical works (Also, let's discuss that word!) deal with.

-

Theme

Theme = the big idea or core concept in the work.It's not the plot. It's the meaning underneath the story.In an exegesis, theme = what central idea shaped your creative work.

-

Message

Message = what the work wants the viewer to understand or feel.It is more specific than theme.

Theme = death and fearMessage = Even when life is painful, beauty can still guide you forward.

Your story about the girl afraid of death has:

-

Theme: fear of mortality, fragility of life

-

Message: Art and imagination can bring meaning when life feels overwhelming

-

Purpose

Purpose = why the work was created.

I create to explore emotion and beauty through colour, fantasy, and symbolism.

I create to learn animation skills and understand my own creativity.

Purpose is always tied to YOU as the practitioner.

-

Creative process (ideation and inspiration, production and even distribution)

Creative practice research cares deeply about how a thing was made.

Process part are:

-

Ideation & Inspiration: moodboards, references, experimentation and research/reading.

-

Production: technical workflow

-

Distributioin: Where and how it be presented

Even thinking about distribution affects design decisions.

I create because I love bringing beauty to life and building my own worlds through character design and animation. My practice focuses on developing high-quality 2D and 3D characters and exploring how they can express personality, emotion, and story. Guided by the concept of embodiment—the idea that movement can give life to form—I aim to transform my designs into living, expressive beings. Creating is both a passion and a challenge: it allows me to prove to myself what I can achieve while enjoying the process of making something uniquely my own. Through continuous learning and experimentation, I hope to combine skill, imagination, and storytelling to craft characters that resonate visually and emotionally with audiences.

ChatGPT. (2025). Creativity character sheet [AI-generated image]. OpenAI.

This lo-fi character sheet demonstrates the early stages of my creative practice and directly reflects the themes in my artist statement. My practice focuses on bringing beauty to life through character design and animation, and this prototype allowed me to explore how a character’s personality can emerge through simple shapes, poses, and expressive details. Even though the drawing is minimal, the process helped me understand how embodiment works on a small scale—how posture, silhouette, and gesture can already make the character feel alive (Young, 2023).The lo-fi format also supported experimentation without pressure. Because I was not aiming for a polished final artwork, I could focus on ideation: testing proportions, exploring visual motifs related to creativity (such as flowing lines, spark-like shapes, or exaggerated expressive features), and experimenting with how the character might move. This aligns with my statement that creativity is both a passion and an ongoing challenge. The prototype reminded me that creating expressive characters begins long before detailed rendering or animation—life starts in these early sketches.Finally, producing this work reinforced my intention to build worlds and emotional resonance. Even with simple lines, the character began to suggest story and personality. This confirms that my creative process—combining imagination, skill development, and emotional exploration—is fundamental to how I approach my practice. The lo-fi sheet is not just a test drawing; it represents the foundation of how I transform ideas into living, believable characters.

Reference (APA 7)

-

Young, A. (2023). Embodiment in animated character design. Animation Studies Journal, 18(2), 45–57.

Week 6

Truly beautuiful

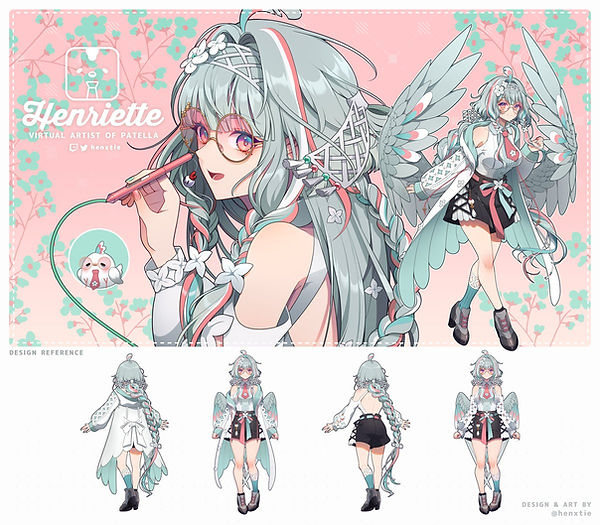

Hen-tie. (2022, July 12). My new reference sheet for my VTuber + sneak peek of my model [Illustration]. Twitter. https://x.com/henxtie/status/1546534269673021441?s=20

As a VTuber artist, Hen-tie is deeply immersed in digital avatar culture. This implies a habitus shaped by online communities, live streaming, and character-based identity work.This reflective of someone who navigates the “field” of VTuber / digital performance, where visual design, character identity, and online presence are central.Character Design & Embodied IdentityThe reference sheet suggests a strong concern for character “look,” “pose,” and personality — an embodied way of designing.This aligns with Bourdieu’s idea of habitus as “dispositions … schemes of perception and action” shaped by years of practice. Her creative decisions (how to design the character) are informed not just by personal taste but by what works in the VTuber performance / streaming context (e.g., appealing design, recognisability).

Hen-tie’s character design reflects a deeply embodied and socially informed habitus — she doesn’t just draw characters, but designs performative identities. Her work sits at the intersection of digital culture, online performance, and visual creativity. The way she plans her avatar with detailed reference sheets suggests she values intentionality, presence, and coherence in her character’s form and expression.This resonates strongly with my own creative habitus as an animator: like Hen-tie, I think of characters not just as shapes, but as living beings shaped by a field (for me, that’s animation, fantasy, or VTuber-inspired design). Her disposition toward disciplined design, careful planning, and avatar identity influences how I see my own process. I feel encouraged to build my character designs with both vision and structure, balancing imaginative freedom with practical considerations of how my characters “live” in their creative worlds.

Truly ugly

u/cheese_flavored. (2023, May 28). Ugly character art. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/DnD/comments/ctvjh0/ugly_character_art/ Reddit

The Habitus of this image

Most people prefer beautiful art over “ugly” art, and I’m also one of them. The image from the Reddit post is not my personal style — I don’t really like this type of “ugly” character design. However, that doesn’t mean no one likes it. Different people appreciate different aesthetics, and some artists love exaggerated, strange, or intentionally imperfect characters.

For me, I prefer designs that are cute, appealing, or colourful. If the “ugly” character were drawn in a more cartoon or stylised way, I might enjoy it more. Even though it’s not my style, I can still understand how this kind of art fits within a creative habitus where personality, humour, and expressiveness matter more than beauty.

The drawing intentionally embraces “ugliness,” which means the artist:

-

rejects the polished, idealised fantasy styles common in mainstream RPG art

-

values character, humour, and individuality over beauty

-

feels comfortable breaking aesthetic “rules”

-

This reflects a habitus shaped by communities that appreciate authenticity, quirkiness, and imperfect charm — especially Reddit art communities, indie RPGs, and meme-based art culture.

This artwork grows from a habitus shaped by fantasy roleplaying culture, online art communities, and a playful approach to character design. Instead of aiming for idealised beauty, the artist embraces expressive imperfections, exaggeration, and humour — core values in the D&D creative field. Their spontaneous, sketch-driven style reflects a disposition toward experimentation and storytelling rather than technical refinement. The character’s “ugliness” becomes a creative choice that celebrates individuality and personality, mirroring the artist’s investment in the diverse, inclusive, and imaginative spirit of tabletop worlds.

Artist Statement

-

My creative practice is shaped by a love of beauty, colour, and expressive character design. I enjoy creating worlds through 2D and 3D animation where characters feel alive through their gestures, emotions, and movement. Soft colours, cute forms, and fantasy elements inspire me because they bring comfort and joy, both to myself and to others. I create to explore emotion, improve my skills, and express ideas that are sometimes difficult to put into words.

-

While I know that some artists enjoy “ugly” or exaggerated character styles, this is not the direction I naturally connect with. I prefer designs that are appealing, stylised, and visually harmonious. If unusual or “ugly” characters are drawn in a more cartoon-like or expressive way, I may appreciate them more—but my personal habitus draws me toward beauty, imagination, and emotional resonance

-

My goal is to blend technique, creativity, and storytelling to create characters that feel genuine and memorable. Through continuous practice and experimentation, I hope to build worlds and designs that invite viewers to feel something—comfort, curiosity, or wonder—through the beauty and personality of the characters I create.

Week 8

What is Open work?

Easy way to say it is mean the works that are quite literally 'unfinished'.

So that can give reader or audience more interpretive possibilities.

Ok, Now can show you my Open Work.

I will explain the creative choices on my work, but I divided it into scene setting, character setting and action setting.

Brief explanation of the work.

This animation is tell a person's life.

The life that include: friend, works, learning, and feeling lost about the future.

The scene setting

The scene setting in my animation is created and adjusted based on the theme, storyline, and mood of the music. For this project, the music guided the emotional tone of each scene, and I used semiotic concepts to design imagery that functions as meaningful signs for the audience.

1. Sakura Tree (Cherry Blossom)

I chose to open the animation with a Sakura tree because it carries strong cultural connotations of beauty, fragility, and the fleeting nature of life (Barthes, 1964/1977). The falling petals act as signifiers of impermanence, symbolising the beginning of a journey that is both beautiful and temporary. At the denotative level, it is simply a tree; at the connotative level, it represents the delicate transition from life into time passing (Saussure, 1916/2011).

2. Life Line

The second scene visualises the idea that life is finite. I designed a long line for the character to stand on, symbolising the human life path. The distant coffin at the end acts as a powerful symbolic sign that represents mortality—an inevitable fact that cannot be changed. Even though the character sees the ending ahead, she continues to walk forward, which connotes courage, acceptance, and the will to live despite fear. This aligns with semiotic ideas about how symbols create layered emotional meaning beyond their literal form (Barthes, 1964/1977).

3. Memoir (Memory and Connection)

The third scene expresses what gives life meaning: companionship, emotion, and shared experiences. I visualised this by showing the main character playing with friends. These actions work as behavioral codes that signify joy, support, and emotional memory. At the denotative level, they are simply characters interacting; connotatively, they communicate the idea that relationships form the “treasures” of life.

By using semiotics in my scene design, I make sure each visual element carries a clear emotional message. Each setting acts as part of a visual language, guiding the audience to understand the deeper themes of life, fear, and meaning without needing dialogue.

APA 7 Reference List

-

Barthes, R. (1977). Image, music, text (S. Heath, Trans.). Fontana Press. (Original work published 1964)

-

Saussure, F. de. (2011). Course in general linguistics (C. Bally, A. Sechehaye, & A. Riedlinger, Eds.; W. Baskin, Trans.). Columbia University Press. (Original work published 1916)

Character setting

Every time I create a character, the first thing I decide is the theme of the character. This theme becomes the core signified—the concept or meaning I want the audience to understand (Saussure, 1916/2011).

After that, I search for visual materials and references, because I want to design clear signifiers such as shapes, colours, silhouettes, and symbols that communicate the character’s identity visually. My goal is for the audience to recognise what kind of character it is without needing verbal explanation.

Using semiotic theory, I think about how each design choice functions as a sign. Elements like colour palettes, clothing, or props operate through cultural codes that guide the viewer’s interpretation (Barthes, 1964/1977). For example, a sharp silhouette may connote danger or strength, while soft, rounded shapes may connote cuteness or safety.

By choosing the right signs and arranging them carefully, I create a visual language that allows the character’s personality and role to be understood at both the denotative (literal) and connotative (symbolic or emotional) levels (Barthes, 1964/1977). Semiotics helps me ensure that my character “speaks” to the viewer through design, not through words.

APA 7 Reference List

-

Barthes, R. (1977). Image, music, text (S. Heath, Trans.). Fontana Press. (Original work published 1964)

-

Saussure, F. de. (2011). Course in general linguistics (C. Bally, A. Sechehaye, & A. Riedlinger, Eds.; W. Baskin, Trans.). Columbia University Press. (Original work published 1916)

Action setting

When I animate a character’s actions, I treat every movement as a sign that communicates meaning. In semiotic terms, a character’s body, posture, and gestures become signifiers that express specific emotions, attitudes, or intentions—the signifieds the audience interprets (Saussure, 1916/2011). Even small movements, such as a hand tremble, a downward gaze, or a tightened jaw, carry connotative meanings that go beyond the literal action.

I also consider cultural and behavioural codes, which help viewers instantly recognise emotional states. For example, crossing the arms may connote defensiveness, leaning forward may connote confidence, and avoiding eye contact can signify shyness or anxiety (Barthes, 1964/1977). These actions create a visual language that allows the audience to understand the character without dialogue.

APA 7 Reference List

-

Barthes, R. (1977). Image, music, text (S. Heath, Trans.). Fontana Press. (Original work published 1964)

-

Saussure, F. de. (2011). Course in general linguistics (C. Bally, A. Sechehaye, & A. Riedlinger, Eds.; W. Baskin, Trans.). Columbia University Press. (Original work published 1916)

Week 9

THIS WEEK:

-

We get started on the CIM417.2 Micro-Research Project

-

We discuss experimentation as a way of framing Creative Practice Research, and

-

Revisit epistemology, thinking through the production of knowledge in creative research

CIM417.2 Micro-Research Project,

I chose the question 3 for my Micro-Research Project.

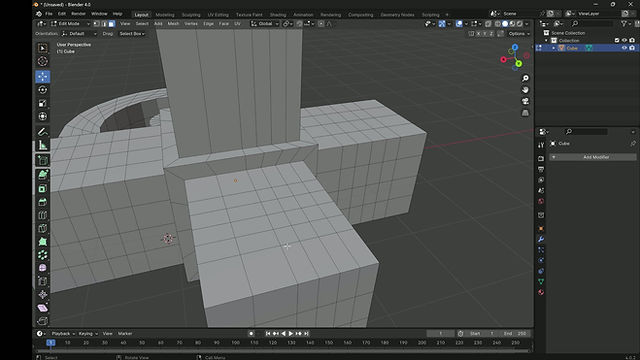

The technology that I going to using is call the Bledner.

Question 3's task need to do, Take notes, Screensho....... this is infor you need to keep handy.Literature to investigate:

- Technology/media

What is Blender?

Blender is a free and open-source 3D creation suite that supports the entire digital production pipeline, including modelling, sculpting, rigging, animation, simulation, rendering, compositing, and video editing (Blender Foundation, n.d.). Because of this broad functionality, Blender is used across many creative fields such as animation, game development, visual effects, product visualisation, motion graphics, and 3D printing (PAACADEMY, 2023). As an open-source tool, Blender is accessible to both professionals and beginners, allowing artists to experiment freely without software cost barriers (Blender Foundation, n.d.). This versatility has made Blender widely adopted in creative communities, where users often share examples of using Blender for illustration-style rendering, stylised animation, architectural visualisation, and personal artistic experimentation (Learntube, n.d.; Blender Artists, n.d.; Reddit, 2023).

APA 7 Reference List:

- Blender Foundation. (n.d.). About Blender. https://www.blender.org/

-Blender Artists. (n.d.). What do you use Blender for? https://blenderartists.org/t/what-do-you-use-blender-for/455151/13

-Learntube. (n.d.). What is Blender used for? A list of reasons to use Blender. https://learntube.ai/blog/design-creative/blender/what-is-blender-used-for-a-list-of-reasons-to-use-blender/

-PAACADEMY. (2023). What is Blender 3D used for? https://paacademy.com/blog/what-is-blender-3d-used-for

-Reddit. (2023). What professions use Blender? https://www.reddit.com/r/blender/comments/16vki19/what_professions_use_blender/

-Technological determinishm

Technological determinism argues that digital tools shape how people create, implying that the design and affordances of a technology strongly influence the final outcome (McLuhan, 1964; Winner, 1986). From this perspective, a software like Blender might be expected to determine the kinds of models, animations, and visual effects an artist produces. However, scholars such as Williams (1974) emphasise that users also exercise agency by adapting, repurposing, or resisting technological expectations. My own creative process reflects this more flexible view. Although I often learn new skills by watching tutorials, I rarely reproduce the technique exactly as taught. Instead, I apply the tools in unintended ways—for example, using modelling tools for effects they were not designed for, or experimenting with physics simulations until unexpected results appear. Accidental outcomes or unplanned experimentation frequently lead to new ideas. These practices suggest that while Blender provides certain constraints, it does not strictly determine the artistic outcome; instead, creative agency emerges through reinterpreting or misusing the tools.

APA 7 Reference List:

- McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. McGraw-Hill.

- Williams, R. (1974). Television: Technology and cultural form. Fontana.

- Winner, L. (1986). The whale and the reactor: A search for limits in an age of high technology. University of Chicago Press.

- Constraints/limitations (creativity theory)

1. Learning from tutorials but changing the technique

- Constraint = tutorial only teaches one method.

- Your creativity = invent your own way.

2. Accidents inspiring new ideas

- Constraint = unintended results, tool behaves differently.

- Your creativity = using accidents as inspiration.

3. Modelling without planning

- Constraint = you do not have a clear direction at first.

- Your creativity = exploring through the tool’s unexpected effects.

4. Blender’s tools not doing exactly what you want

- Constraint = tool limitations (fluid, rigging, modifiers).

- Your creativity = trying alternatives, combining tools, problem-solving.

Creativity theorists argue that constraints are not obstacles but catalysts for innovation. Stokes (2006) suggests that limitations encourage creators to explore alternative approaches, while Boden (2004) emphasises that novel ideas often emerge when individuals push against the boundaries of what tools allow. In Blender, constraints appear through technical limitations, unexpected tool behaviours, and the artist’s own developing skill level. These restrictions frequently shape my creative process. For example, when a tool does not produce the expected result, or when a simulation behaves unpredictably, I often discover new visual effects or ideas. Similarly, learning techniques through tutorials provides only a starting point; the constraint of a fixed method motivates me to adapt the technique in ways not originally taught. Even unplanned modelling sessions, where I explore tools without a clear design, allow limitations and accidents to guide my creativity. These experiences support the view that constraints within Blender do not hinder artistic creation but instead stimulate experimentation and creative problem-solving.

APA 7 Reference List:

- Boden, M. A. (2004). The creative mind: Myths and mechanisms (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. HarperCollins.

- Stokes, P. D. (2006). Creativity from constraints: The psychology of breakthrough. Springer.

Comparative works/artists. Who else has experimented with creative use of technology:

- in your discipline

- in similar disciplines

Arts of Blender

Why he fits your topic:

SouthernShotty uses Blender to make stylised, cartoon-like 3D that breaks Blender’s usual “realistic rendering” purpose. Blender is often used for realistic animation or VFX, but he intentionally goes the opposite direction.

This supports your argument:

- Blender doesn’t determine the outcome — the artist chooses how to bend the rules.

- Kevandram

Why he fits your topic:

- Blender is primarily designed for 3D modelling, realistic rendering, and animation, yet Kevandram uses the Grease Pencil tool—which was originally created for 2D drawing and annotations—to construct immersive 3D scenes. His work highlights the value of experimenting with digital tools, adapting them, and pushing them outside their conventional functions. This directly aligns with the project’s focus on discovering what can be gained through non-standard or experimental uses of creative technology.

This supports your argument:

- Kevandram’s process supports the central argument of this research: that unexpected or unintended uses of digital tools can lead to innovation, new aesthetics, and new forms of meaning-making. He demonstrates that creative breakthroughs often emerge not from following tutorials or sticking to the “correct” workflow, but from experimenting with tools in open-ended ways.

- 3D Tudor

Why he fits your topic:

3D Tudor teaches Blender modelling but often encourages alternative approaches, showing that there is no single “correct” way to use the tools.

Creative/experimental aspects:

- Uses simple geometry to create complex environments.

- Repurposes modelling tools for speed workflows.

- Teaches how constraints (low poly, time limits) can become part of the artistic style.

This supports creativity theory:

- Constraints (like low poly limits) lead to new aesthetic styles.

An academic paragraph:

Several contemporary Blender artists demonstrate how creative practices often emerge from using technology in ways beyond its intended purpose. For example, SouthernShotty is known for developing stylised and highly simplified 3D characters that deliberately reject Blender’s usual focus on realistic rendering, instead using shaders, lighting tricks, and unconventional modelling approaches to produce a distinct cartoon-like aesthetic (SouthernShotty, n.d.). Kevandram similarly pushes Blender’s creative potential by using the Grease Pencil tool to transform 2D drawings into immersive spatial scenes. His workflow blends flat, hand-drawn strokes with three-dimensional models, producing hybrid illustrated worlds that extend 2D art into 3D environments, highlighting how Blender’s tools can be repurposed to support new forms of world-building (Kevandram, n.d.). In a different but related way, 3D Tudor demonstrates how constraints can encourage creative experimentation by teaching alternative modelling workflows, low-poly techniques, and unconventional combinations of tools that simplify the production process while generating unique stylistic results (3D Tudor, n.d.). Together, these artists show that Blender’s technological affordances do not strictly determine outcomes; instead, creative users reinterpret and bend the software’s tools to produce innovative and unexpected artistic possibilities.

APA 7 Reference List:

-

3D Tudor. (n.d.). 3D modelling and Blender tutorials. https://3dtudor.com/

-

Kevandram. (n.d.). Kevandram digital art portfolio. https://www.kevandram.com/

(Use whichever official site/social link your project requires.) -

SouthernShotty. (n.d.). SouthernShotty stylised 3D art and tutorials. https://southernshotty.com/

Analytical task:

Use the language of semiotis to analyse the differences you pereceive in specific works that use technology in diferent ways:

Two works that demonstrate contrasting technological approaches are Kevandram’s 2D–3D hybrid Grease Pencil scenes and SouthernShotty’s stylised 3D character models. Although both rely on Blender, their visual languages differ significantly. Using semiotics, these differences reveal how the artists’ technological choices shape meaning.

Denotatively, Kevandram’s work displays hand-drawn lines, sketch-like textures, and flat illustrated shapes arranged within a 3D environment. The viewer sees scenes that look as if they were drawn in a sketchbook but then expanded spatially. In contrast, SouthernShotty’s work presents rounded, simplified 3D forms, smooth shading, and stylised lighting that resembles clay, plastic, or soft toy-like characters. His worlds appear fully three-dimensional and animated, with clear volume and depth.

The signifiers in each work communicate different signified meanings. Kevandram’s visible pen strokes, layered 2D planes, and textured linework act as signs of “hand-made” illustration, signifying artistic expressiveness, imagination, and the blending of traditional drawing with digital space. SouthernShotty’s smooth surfaces, exaggerated proportions, and clean digital materials act as signifiers of playfulness, humour, and the childlike charm often associated with cartoon aesthetics. The technological tools chosen — Grease Pencil versus stylised 3D modelling — become signs that communicate different artistic intentions.

These differences also generate distinct connotations. Kevandram’s hybrid 2D–3D scenes connote creativity, experimentation, and magical realism, as the illustrated strokes feel alive within a digital world. The combination of flatness and depth produces a dreamlike atmosphere, suggesting that imagination can cross boundaries between drawing and digital space. By contrast, SouthernShotty’s soft 3D characters connote friendliness, simplicity, and accessibility. His visual codes echo children’s animation and toy design, inviting viewers into a world that feels safe, playful, and emotionally warm.

Finally, the artists’ technological approaches underpin their visual meanings. Kevandram uses Blender against its original purpose — transforming 2D drawings into spatial environments — which produces meanings centred on hybridity, innovation, and breaking software boundaries. SouthernShotty uses Blender’s modelling and rendering tools intentionally but stylises them heavily, showing how constraints of low-poly shapes and simplified materials can still create expressive, character-driven narratives. These comparisons illustrate that different uses of technology do not only change visual style; they change the meanings, emotions, and cultural codes communicated by the artworks.

Week 10

- your key concepts and literature: Are there gaps in your literature?

- your proposed creative experiments: Are your experiments experimental enough (have they been done before)?

Build-your-own methodology.

Methodology Section Part

This micro-research project employs a Creative Practice Research (CPR) methodology in which knowledge is produced “in and through the acts of creating and performing” (Borgdorff, 2010, p. 46). The research paradigm assumes that knowledge in creative contexts is situated, subjective, and shaped by the artistic process rather than universal or generalisable. In CPR, the artwork itself functions as a form of knowledge, and reflective practice becomes a key method for revealing tacit insights—emergent understandings that arise during making but may be difficult to articulate in purely theoretical terms. By engaging directly with Blender through iterative experimentation, I position my creative process as both a method of inquiry and a site of knowledge production.Leavy (2015) describes arts-based research as a “set of methodological tools” rather than a fixed procedure, emphasising that these tools involve processes of data generation, analysis, interpretation, and representation (p. 4). Similarly, Borgdorff (2006) argues that experimentation in creative practice serves not only to develop artworks but also to reveal tacit knowledge about practice itself (p.16). In my project, I experiment with Blender tools such as modelling systems, Grease Pencil, rigging, physics simulations, and stylised shaders to investigate what can be gained by using creative technologies in unintended ways. My methodology therefore includes adapting tutorial techniques, exploring tools beyond their standard functions, and responding to accidental results that occur during making. These actions generate experiential data about how technological constraints and unexpected tool behaviours can support creative innovation and meaning-making within digital art practice.

APA 7 Reference List:

- Borgdorff, H. (2006). The debate on research in the arts. Amsterdam School of the Arts.

- Borgdorff, H. (2010). The production of knowledge in artistic research. In M. Biggs & H. Karlsson (Eds.), The Routledge companion to research in the arts (pp. 44–63). Routledge.

- Leavy, P. (2015). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Week 11

Linked in the RESOURCES tab is a series of short self-paced lessons on writing and editing. Take a look at these and discuss.

Week 12

Lattice part

Tree or Libra-Tree

Spiral Column

Celestial Ring