CIM416 Intercultural Studies

Week 1 - A discourse approach

My mindmap is show who am I and what I interested. And that is all. It seen like simple.

How is this structure me to understanding of the world, um..........

Ok, what is my art stlye, cute right? In fack is japanese anime style, but if I want, I can use other culture's style on my art. Because I like to creat art or my own work, and that make me to more understand in different culture's style. Let me more understanding of the world.

Reading one : White Privilege.

White privilege can be defined as the implicit societal advantages afforded to White people relative to those who experience racism. (Racism No Way, n.d.)

So is White privilege good word?, I think it depends on who uses this word to get privilege. 'White privilege' give feel that White race are higher than others, they are the best, they do anything is all good, they are proud that they are the white people. So this word is good for them, but to other racm is not, it is unfair. White privilege is the legacy of apartheid, which subjugated and devalued anyone whose skin colour was not white. Despite the political dismantling of apartheid, white privilege persists. (Davids et al., 2021)

Reading 2: Scollon, Scollon & Jones.

About the "Scollon, R., Scollon, S. W., & Jones, R. H. (2012). Chapter 1: What is a discourse approach" I had saw this sentence:

" language is fundamentally ambiguous " (Scollon et al., 2012. pag 11)

I agree this sentence and in the chapter use example is excatly show this (Scollon et al., 2012. pag 10-11). When this thing happen, that could be communication barriers.

When you tell someone what you think, but they understand it in the wrong way. This is not anyones mistak, the reson to make this thing happen are linguistic and cultural practices or employ disparate communication styles (Abrams, 2020). So miscommunication is not a matter of ‘if’ but ‘when.’ (Abrams, 2020)

Reference List

-

Racism No Way. (n.d.). What is white privilege? An overview. Retrieved August 26, 2025, from https://racismnoway.com.au/about-racism/understanding-racism/white-privilege/

-

Davids, N., Tyson, K., Driscoll, K., Della Sudda, M., Terriquez, V., & Zayas, V. (2021, September 13). White privilege: What it is, what it means and why understanding it matters. The Conversation. Retrieved August 26, 2025, from https://theconversation.com/white-privilege-what-it-is-what-it-means-and-why-understanding-it-matters-166683

-

Naik, A. R., Baker, S., & Mohiyeddini, C. (2023, November). What is culture? Frontiers for Young Minds, 11, Article 1150335. https://doi.org/10.3389/frym.2023.1150335 (Naik, Baker, & Mohiyeddini, 2023)

-

Abrams, Z. I. (2020). Miscommunication, conflict, and intercultural communicative competence. In Intercultural Communication and Language Pedagogy: From Theory to Practice (pp. 288–312). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108780360.014

-

Scollon, R., Scollon, S. W., & Jones, R. H. (2012). Intercultural communication: A discourse approach. John Wiley & Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sae/detail.action?docID=7103430

Week 2 - Intercultural sensitivity training

According to Bennett’s (1986) Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS), individuals move along a continuum from ethnocentrism—where one’s own culture is central—to ethnorelativism—where cultural differences are acknowledged, respected, and valued. Um, I think I don't have any about the example of intercultural sensitiviy experience for illustration, but in the life have a lot of intercultural sensitiviy news. Like:- 2021- 'Valentino' model - Koki trampling kimono-belt cause (South China Morning Post, 2021). In the advertisement, Kōki appeared to trample on a fabric resembling a kimono belt (obi) while wearing shoes indoors. Many people in Japan criticized the campaign as culturally disrespectful because the obi is a traditional garment symbolizing beauty and heritage, and wearing shoes inside is considered impolite (South China Morning Post, 2021). When I first encountered this story, I did not immediately understand why it caused such strong reactions. However, through reflection, I realized that my initial response reflected Bennett’s (1986) Minimization stage—assuming that universal ideas of creativity and artistic freedom were more important than cultural context.

This image is made by ChatGPT

If we want to create meaningful and ethical creative projects that explore intercultural themes, we must first understand what productive intercultural engagement looks like. Bennett’s (1986) Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) provides a useful framework for this process. It helps us recognise our own position on the continuum from ethnocentrism to ethnorelativism, showing how our perceptions of cultural difference affect our communication and creative choices. By becoming more aware of our assumptions, biases, and emotional reactions to cultural difference, we can learn to respond with empathy and respect. This awareness is essential for ethical intercultural collaboration, as it allows us to engage with other cultures not as objects of inspiration or imitation, but as equal partners in dialogue and creative exchange.

Reference List

-

Constructivism-IDRI.pages - CIM416 week 2 reading.pdf

-

(PDF) A developmental approach to training for intercultural sensitivity

Week 3 - Bourdieu

Maton, K. (2014). Habitus. In M. Grenfell (Ed.), Pierre Bourdieu: Key concepts. Taylor & Francis

= The book Pierre Bourdieu: Key Concepts is designed to explain Bourdieu’s main ideas in an accessible way, including concepts like capital, field, symbolic power, and habitus.

Webb, J., Schirato, T., & Danaher, G. (2002). Chapter 2, Cultural field and the habitus. In Understanding Bourdieu. SAGE Publications, Limited.

= The chapter explains how habitus interacts with the field: your dispositions (habitus) influence how you navigate the field, and the field, in turn, shapes your opportunities and behaviors.

Two key Bourdieu concepts: the cultural field and habitus.

When I first came to Australia from Taiwan in 2012, one thing that felt very different was how students changed classrooms for every subject. In Taiwan, except for physical education and computer class, students usually stay in the same classroom while teachers come to us. When I started studying in Australia, I had to move between classrooms according to the timetable. Even though I understood the schedule, I often felt a bit confused about finding the right classroom. I also needed to carry my school bag and books to every class, which felt strange at first, because in Taiwan we usually keep our bags and things in the main classroom.

This experience helped me realise that different education systems reflect different cultural values. The Australian system encourages independence and personal responsibility, while the Taiwanese system focuses more on group belonging and stability. Webb, Schirato, and Danaher (2002) explain that our behaviour and expectations are shaped by the “field” we grow up in—each field has its own rules and ways of doing things that feel natural to us. My confusion came from moving from one educational field to another, where my familiar habits no longer fit perfectly. Maton (2014) further notes that habitus is not fixed but can change when we enter new contexts. Over time, my habitus adjusted as I became more confident and comfortable moving between classrooms and managing my own learning in Australia.

Reference List:

-

Maton, K. (2014). Habitus. In M. Grenfell (Ed.), Pierre Bourdieu: Key concepts (2nd ed., pp. 48–64). Routledge.

-

Webb, J., Schirato, T., & Danaher, G. (2002). Understanding Bourdieu. SAGE Publications.

Week 4 - Representation

Make a collage of representations of a particular kind. See if you can let your collage express your critical viewpoint without the need for words.

Traditional Chinese ink painting values simplicity, emptiness, balance, and the spirit of nature — beauty comes from feeling, flow, and suggestion.

In contrast, European oil painting (especially from the Renaissance to modern realism) values detail, perspective, light, and realism — beauty comes from precision, proportion, and mastery of form.

Can you express your view without simply resharing or rearticulating problematic representations?

Yes — but it takes awareness and intention.

When you express your view about cultural or artistic issues, it’s easy to accidentally repeat the same stereotypes or biased images you’re trying to talk about. The key is to show awareness of the problem and to reframe or challenge it through your work.

Don’t just show the stereotype — show your attitude toward it.

For example, if you include a Western painting that idealizes white beauty, you could contrast it with a Chinese ink portrait that celebrates natural imperfection.

- Use visual contrast, irony, or questioning to guide viewers to your message.

(e.g., placing a “perfect” Western portrait next to expressive brushstrokes that feel more alive — this shows your critique.)

- Add context. A short caption or title can help viewers understand that you’re critiquing a representation, not repeating it.

What is the difference between perpetuating a stereotype and critiquing it?

Perpetuating a stereotype

- Repeats the image or idea

without questioning it.

- Reinforces existing beliefs.

- Makes the stereotype look

"normal" or "true."

- Example: Showing Western art

as the "most beautiful."

- Viewer reaction: accepts the

stereotype.

Critiquing a stereotype

- Shows or references the stereotype to reveal its problem

- Challenges or rethinks those beliefs

- Exposes how it is constructed, limited, or harmful

- Example: Juxtaposing Western art with Chinese ink to show different ideas of beauty

- Viewer reaction: reflects on why the stereotype exists

Week 5 - Postcolonialism

As a Taiwanese person, I identify more with the colonised rather than the coloniser. Taiwan’s history includes periods under Japanese colonial rule (1895–1945) and long influences from both Chinese and Western powers. This background means that questions of cultural identity are always complex — Taiwan has absorbed elements from many cultures, yet still struggles for international recognition. Living with this postcolonial legacy shapes how I see my relationships with others. When I collaborate or communicate with people from dominant cultures, I sometimes feel a sense of cultural negotiation — balancing between showing my own background and adapting to global norms.

Colonialism is not just about war, racial violence and death: As Apocalypse Now and the book on which it is based, Heart of Darkness demonstrate, it can also lead to questions about identity and the construction of self in relation to an Other.

1. Edward Said – Orientalism (1978)

In the introduction to Orientalism, Edward Said examines how the West has historically constructed the East—or the "Orient"—as a monolithic, exotic "Other" to assert Western superiority. He argues that this portrayal is not based on objective reality but on a discourse that serves political and imperial interests. Said emphasizes that knowledge about the Orient is produced by Western scholars, artists, and policymakers, who shape and control its representation. This process, termed "Orientalism," involves creating a false dichotomy between the rational, developed West and the irrational, backward East. Said's work challenges readers to recognize how cultural narratives can perpetuate power imbalances and colonial dominance.

Reading 2 : Can the subaltern speak?

2. Gayatri Spivak – “Can the Subaltern Speak?” (1988)In this influential essay, Gayatri Spivak critiques the ability of marginalized groups, particularly women in colonized societies, to have their voices heard within dominant discourses. She argues that even well-meaning intellectuals often speak "for" the subaltern, thereby silencing them further. Spivak uses the example of the British colonial justification for the practice of Sati (widow immolation) to illustrate how Western narratives can misrepresent or erase the agency of subaltern individuals. Her provocative conclusion, "the subaltern cannot speak," underscores the structural limitations that prevent marginalized voices from being truly heard and understood.

Spivak examines whether subaltern groups—the most marginalized people in society, especially in colonized contexts—can have their voices heard in political, academic, or cultural discourse. She asks: Can they truly “speak” for themselves, or does the act of speaking get mediated and distorted by those in power?

-

Subaltern: A term borrowed from Antonio Gramsci, referring to people who are socially, politically, and geographically outside the power structures of society. In Spivak’s focus, this includes colonized women, peasants, and other marginalized groups.

-

Main question: Even when we “listen” to the subaltern, do we actually hear them, or are we just hearing a version filtered through the voices of elites, academics, or colonial authorities?

Reference List

-

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism (Introduction). Pantheon Books. https://ia600800.us.archive.org/33/items/6-said-1978-orientalism-introduction/6%20Said%201978%20Orientalism%20introduction_text.pdf

-

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. 271–313). University of Illinois Press. https://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~sj6/Spivak%20CanTheSubalternSpeak.pdf

Week 6 - Globalisation

In my day's reflecting that possible through "Globaliation.

Throughout my day, I can see how globalisation quietly shapes the things I do, watch, and create.

In my free time, I like watching AI story videos on YouTube. These videos often mix different themes — palace fighting, time travel, doomsday, and ghost stories — showing how storytelling across cultures and genres can blend through global digital platforms. YouTube itself is a global space where creators from all over the world share content. Even the AI technology that generates these stories comes from international collaborations in software development and machine learning, which rely on global data and infrastructure. I usually play these videos while doing art or other work, because they help me concentrate and feel inspired.

When I create art, I often search for images online to find new ideas. The internet gives me access to endless visual materials from different countries and cultures. This process reflects globalisation in the way artistic resources and inspiration flow freely across borders. Sometimes, unexpected images or styles from other cultures influence my work and help me solve creative problems in new ways. These small discoveries show how global visual culture can shape individual creativity.

The music I listen to also shows the power of globalisation. My playlist includes animation soundtracks, and songs in English, Japanese, and Mandarin. Through global streaming platforms, I can easily access music from different parts of the world. This mix of languages and styles reflects how cultural exchange has become a normal part of daily life.

For dinner, I cook simple but comforting dishes like stir-fry, soup (chicken, pork, or miso), meat, and salad. These foods come from different cultural traditions — for example, miso soup has Japanese origins, while stir-fry comes from Chinese cuisine. Even the ingredients I use, such as imported sauces or seasonings, are products of international trade and food distribution systems. Cooking these meals connects me to global food cultures and economies.

Overall, I was actively involved in all these activities — watching videos, making art, listening to music, and cooking. Although these routines feel ordinary, they are made possible by global networks of technology, trade, and culture. Through them, I experience how globalisation allows the movement of stories, sounds, images, and tastes across the world, shaping my everyday creative and personal life.

What is Globalization?

It is a term used to describe the increasing connectedness and interdependence of world cultures and economies (National Geographic Society, 2025).

The Golobalization's Benefits and disadvantags list:

Benefits of Globalization

-

Economic growth: Globalization encourages trade, investment, and technology transfer, which helps many countries boost productivity and expand their economies (Chang, 2024; HelpfulProfessor, n.d.).

-

Access to markets and investment: Businesses can enter international markets, and consumers can enjoy a wider range of goods and services (PoliticalScienceBlog, 2023).

-

Cultural exchange: Increased communication and travel promote cross-cultural understanding and the sharing of creative ideas (Thakur, n.d.).

-

Competition and efficiency: Global competition pushes firms to innovate and improve quality while lowering prices (HelpfulProfessor, n.d.).

-

Technology and knowledge transfer: The global spread of research, innovation, and digital technologies benefits both developed and developing nations (Chang, 2024).

-

Improved living standards: Globalization allows people to access diverse products and services, improving lifestyle and opportunities (HelpfulProfessor, n.d.; Smartling, 2025).

-

Global cooperation: It promotes international collaboration in research, health, and environmental protection (Chang, 2024; Sharabi, 2024).

Disadvantages of Globalization

-

Income inequality: Wealth tends to concentrate in already-developed regions, increasing the gap between rich and poor (Chang, 2024; Smartling, 2025).

-

Loss of local culture: Global media and brands can diminish local traditions and cultural diversity (Thakur, n.d.).

-

Job displacement: Industries often relocate to countries with lower labor costs, causing unemployment in others (HelpfulProfessor, n.d.).

-

Environmental degradation: Globalized production and trade increase pollution and carbon emissions (Thakur, n.d.; Chang, 2024).

-

Loss of national sovereignty: Multinational corporations can influence domestic policy decisions (Thakur, n.d.).

-

Global vulnerability: Economic crises can quickly spread across interconnected global systems (Chang, 2024; Smartling, 2025).

-

Uneven development: Some poorer countries struggle to gain the same benefits due to lack of infrastructure or governance (Chang, 2024).

Reading 1: Globalisation and GothLoli

Monden argues that cultural globalisation does not simply mean one culture (often the West) dominating all others. Instead, he emphasises hybridisation and glocalisation — where global cultural forms are localised, reinterpreted, and fused with local aesthetics (Monden, 2008).

The example of Gothic & Lolita (GothLoli) fashion in Japan shows how Western historical dress and Goth subculture formats merged with the Japanese aesthetic concept of kawaii (“cute”) to become a new hybrid form (Monden, 2008).

Importantly, Monden highlights reverse/“counter-flows” of culture: non-Western styles (like GothLoli) can influence Western youth culture, not just vice-versa (Monden, 2008).

Are there particular western forms that are popular transnationally?

Western forms that are popular transnationally

Many Western-origin animations (e.g., those from Walt Disney Company or Warner Bros.) have global reach: the characters, styles, narratives travel widely. They form a “format” that is adapted, dubbed, localised.

But beyond that, the idea of hybridisation suggests looking at animations that combine Western format + local culture: e.g., a European or American style of hero’s journey but filtered through local mythologies or aesthetics.

Also, consider Japanese animation (anime) which itself has become global: shows like Pokémon or Attack on Titan are adapted for and consumed in multiple cultures. They also get hybridised (local dubbing, remake, fan-adaptation).

In animation, you might look for visual styles (character design, background aesthetics), narrative tropes (transformation, hero vs villain), or thematic structures (good vs evil, redemption) that cross borders.

Are there others that fail to cross cultural barriers?

Going by Monden’s analysis: if a cultural product carries a sense of local aesthetics (e.g., Japan’s kawaii sensibility) and also local social norms (e.g., the subtle signification of youth/innocence in Japan), that may not automatically translate or be accepted in other cultures. For instance, Monden notes that GothLoli’s idea of “cute and demure” is more culturally accepted in Japan than in many Western cultures (Monden, 2008).

Reflection: My Discipline (Animation)

What animations can I create that will be globally viable but still maintain local flavour? The key insight from Monden is to avoid simply imitating a dominant Western style; instead, consider blending a global “format” (e.g., episodic superhero discovery) with local aesthetic or cultural codes (visual style, narrative pacing, character relationships) that give it uniqueness.

Reference List

-

National Geographic Society. (2025, May 29). Globalization. In National Geographic Education. Retrieved August 26, 2025, from https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/globalization/

-

Chang, M. (2024, September 8). Advantages and disadvantages of globalization. Profolus. https://www.profolus.com/topics/advantages-disadvantages-of-globalization/

-

HelpfulProfessor. (n.d.). 30 globalization pros and cons. https://helpfulprofessor.com/globalization-pros-and-cons/

-

PoliticalScienceBlog. (2023, January 6). 10 advantages and disadvantages of globalization. https://politicalscienceblog.com/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-globalization/

-

Sharabi, C. (2024, October 28). The pros and cons of globalization in today’s world. Blend. https://www.getblend.com/blog/the-pros-and-cons-of-globalization-in-todays-world/

-

Smartling. (2025, February 12). Globalization pros and cons: Impact on economies and developing nations. https://www.smartling.com/blog/pros-and-cons-of-globalization

-

Thakur, M. (n.d.). Advantages and disadvantages of globalization. EDUCBA. https://www.educba.com/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-globalization/

-

Monden, M. (2008). Transcultural flow of demure aesthetics: Examining cultural globalisation through Gothic & Lolita fashion. New Voices: A Journal for Emerging Researchers in Japanese Studies, 2(1), 94–105.

https://newvoices.org.au/volume-2/transcultural-flow-of-demure-aesthetics-examining-cultural-globalisation-through-gothic-lolita-fashion/

Week 8 -

The New Global Culture's Track-by-Track Summaries

Gómez-Peña (2001) argues that globalization has created a chaotic cultural landscape where traditional identities collapse, political meaning becomes diluted, and spectacle dominates everyday life. He critiques corporate multiculturalism for turning cultural diversity into a marketable product, while the mainstream bizarre normalizes extreme violence, sexuality, and sensational entertainment. Digital culture creates only the illusion of participation, leaving people politically powerless and emotionally numb. Across global media, art, spirituality, and the body, he shows how modern culture becomes hybrid, commercialized, and desensitized, producing what he calls a global “Social Attention Deficit Disorder.”

APA 7 Reference:

-

Gómez-Peña, G. (2001). The new global culture: Somewhere between corporate multiculturalism and the mainstream bizarre (a border perspective). TDR: The Drama Review, 45(1), 7–30. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1146878

Reading: Elias, Mansouri & Paradies

In Racism in Australia, Elias, Mansouri, and Paradies (2021) explain that racism is not just individual prejudice, but a system of power that structures society. They argue that racism should be understood as a technology of oppression—a set of practices, beliefs, and institutions designed to protect privilege for some groups while disadvantaging others (Elias et al., 2021). This means racism operates even when people do not intend to be racist, because it is embedded in laws, education, media, policing, housing, and everyday interactions.

The authors emphasise that acknowledging racism does not mean Australians are “more racist” than other countries; rather, it means recognising how racism has shaped Australia’s history—from colonisation and the dispossession of Indigenous peoples to the White Australia Policy and contemporary experiences of discrimination (Elias et al., 2021). Racism continues today through structural inequalities, stereotypes, unequal opportunities, and implicit biases.

They highlight that racism is multilevel:

-

Structural racism → unequal policies and institutions

-

Cultural racism → stereotypes, media narratives, national myths

-

Interpersonal racism → everyday discrimination

-

Internalised racism → when marginalized groups adopt negative beliefs about themselves

Finally, the chapter argues that many people in Australia benefit—often unknowingly—from racial privilege, and understanding racism requires reflecting on how power and inequality shape everyday life (Elias et al., 2021).

APA7 Reference

-

Elias, A., Mansouri, F., & Paradies, Y. (2021). Racism in Australia. Palgrave Macmillan.

This week raises questions about whether it is ever possible to study, understand, or represent another culture without reproducing power imbalances. Gómez-Peña (2001) argues that globalisation often turns minority cultures into marketable images, stripping them of political meaning through corporate multiculturalism and spectacle. This aligns with the unit themes of representation, discourse, and postcolonial critique (Hall, 1997; Said, 1978). Elias, Mansouri and Paradies (2021) further show that racism in Australia operates as a structural “technology of oppression,” shaping whose voices are heard or marginalised. These readings suggest that intercultural engagement—whether academic or artistic—can never be entirely neutral and is always influenced by social inequalities and historical power.

Despite these challenges, some global media practices do allow cultural difference to be expressed, particularly when created by Indigenous, migrant, or non-Western authors. This encourages me to think about my own creative practice: instead of simply borrowing cultural elements, I am inspired to approach intercultural work with more reflexivity, respect, and awareness of privilege (Bourdieu, 1990). Ethical creativity is still possible, but it requires careful attention to context, collaboration, and cultural sensitivity.

APA7 Reference

-

Elias, A., Mansouri, F., & Paradies, Y. (2021). Racism in Australia. Palgrave Macmillan.

Week 9

Japan's food

The part about Japanese food connected strongly with me because I already enjoy many traditional dishes, such as sashimi with soy sauce and wasabi. Even though these flavours are simple, they highlight freshness, balance, and respect for the natural taste, which reflects an ontology valuing subtlety and harmony with nature (Allison, 2013; Rath, 2016). Japanese cuisine feels natural and comfortable to me. I also enjoy watching videos of people eating Japanese dishes, like sukiyaki or buckwheat noodles, and I noticed how the pace of eating expresses calmness and appreciation. There is also a cultural tradition in Japan where making a slurping sound while eating noodles shows enjoyment and deliciousness, not rudeness (Bestor, 2018; Cwiertka, 2006).

Another example we discussed is Oden, which I realised is not just a dish but a cultural phenomenon. Oden connects to ideas of seasonality, comfort, and social warmth—often eaten in winter, at food stalls, or convenience stores. It symbolises everyday communal life and the value Japan places on simple, shared food experiences (Richie, 2001). This helped me see that Japanese food is not only about ingredients but expresses a whole cultural attitude toward eating: valuing simplicity, appreciating natural flavours, and finding meaning in shared, seasonal traditions.

APA7 Reference List:

-

Allison, A. (2013). Japanese food culture: Between global trends and traditional values. Cultural Studies Review, 19(1), 45–57.

-

Bestor, T. C. (2018). Taste and tradition in Japanese foodways. Japan Studies Review, 22, 15–29.

-

Cwiertka, K. J. (2006). Modern Japanese cuisine: Food, power and national identity. Reaktion Books.

-

Rath, E. C. (2016). Japan’s cuisines: Food, place and identity. Reaktion Books.

-

Richie, D. (2001). Japanese cuisine: A cultural guide. Tuttle Publishing. (Supports Oden as a cultural/social phenomenon in Japanese daily life.)

Week 10

Japan's Omamori (Luck charm)

This week’s webinar helped me think more deeply about how spiritual objects reflect the worldview of a culture. I found the discussion about Japanese omamori especially meaningful, because it reminded me of the talisman culture in Taiwan, but also showed me how different cultural ontologies shape similar objects in unique ways. Taiwanese talismans are usually yellow-paper charms created through Taoist ritual, often used for healing, protection, or correcting spiritual imbalance (Katz & Shih, 2010). In contrast, Japanese omamori are colourful brocade amulets purchased at Shinto shrines or Buddhist temples, carried casually on bags or phones, and treated as part of everyday life (Reader, 1995). The difference shows how Taiwan’s spiritual practices are more ritual-centred, while Japan’s approach expresses a more integrated, everyday spirituality. Learning this made me reflect on my own habitus as a Taiwanese person—I am familiar with talismans, but I never thought of omamori as spiritually different until now. When we also looked at food traditions like oden or cultural clothing like kimono and hanfu, I realised how material objects—not only art—carry deep meanings about a culture’s values, beliefs, and relationship with the unseen world. This helped me appreciate that intercultural sensitivity comes from recognising differences even in things that look “similar,” and asking what worldview shapes each practice.

APA 7 References:

-

Katz, P. R., & Shih, C. (2010). Divine traces of the Dao: The Daoist canon and its significance. University of Hawai‘i Press.

-

Nelson, J. (2000). Enduring identities: The guise of Shinto in contemporary Japan. University of Hawai‘i Press.

-

Reader, I. (1995). Religion in contemporary Japan. University of Hawai‘i Press.

-

Shirane, H. (2012). Japan and the culture of the four seasons: Nature, literature, and the arts. Columbia University Press.

(Omamori Charm Heritage Japan, n.d.)

(Taiwan Specialties, n.d.)

APA 7 References:

- Taiwan Specialties. (n.d.). Taoist amulet and talisman. TaiwanSpecialties.com. https://www.taiwanspecialties.com/amulet

- Omamori Charm Heritage Japan. (n.d.). Omamori Charm Heritage Japan. https://omamorijapan.com/

Week 11

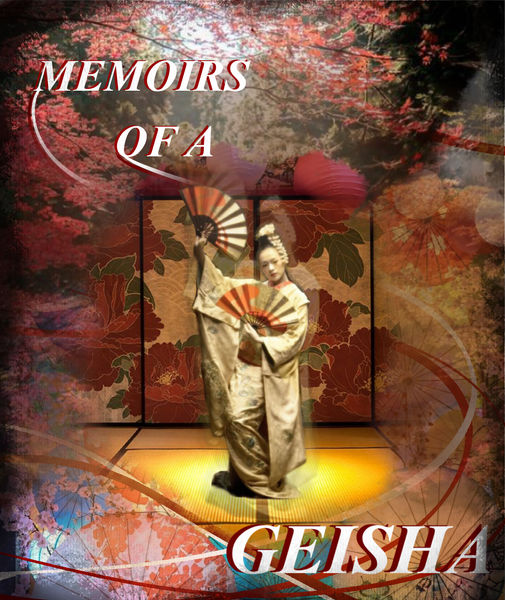

Memoirs of a Geisha (2005) – Movie Poster

The movie poster for Memoirs of a Geisha shows a single pale-faced woman with striking red lips and intense, almost otherworldly eyes. This image turns the geisha into a solitary, mysterious, and sexualised figure, designed to attract a Western audience by emphasising exotic beauty and romantic drama. In contrast, historical and ethnographic accounts describe geisha as highly trained professional artists who work within a community, performing music, dance, and conversation as a sophisticated form of entertainment—not as prostitutes or tragic romantic heroines (Dalby, 1983). Academic analysis of Memoirs of a Geisha argues that both the film and the poster construct an “imaginary Japan” that prioritises fantasy, eroticism, and Orientalist mystery over cultural accuracy (Jin, 2011). Real geisha interviewed in Japanese media similarly criticise the film for reinforcing clichés rather than showing the discipline, skill, and everyday realities of their profession (McCurry, 2005).

APA 7 Reference List (with links)

-

Real geisha life (anthropology book) Dalby, L. (1983). Geisha. University of California Press. https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520257894/geisha

-

Academic analysis of Memoirs of a Geisha and misrepresentation Jin, J. (2011). The discourse of geisha: In the case of Memoirs of a Geisha (Master’s thesis, Lund University). Lund University Publications. https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download fileOId=2166340&func=downloadFile&recordOId=2165854

-

News article with reactions from real geisha to the film McCurry, J. (2005, December 5). Confessions of a geisha. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/dec/06/japan.gender

The article examines how Thai K-pop fans creatively reinterpret Korean pop culture through local symbols and humour. Ferguson and Thanyodom (2024) argue that while K-pop intentionally avoids strong cultural identity to appeal globally, Thai fans—especially the group Deksorkrao—transform K-pop videos into expressions of Thai rural authenticity. Their parody of Blackpink’s Pink Venom replaces luxury imagery with everyday agricultural objects, highlighting contrasts between K-pop’s materialist fantasies and the realities of rural Thai life. The authors suggest this is not just cultural hybridity but a form of authentic cultural expression, allowing young Thais to communicate social critique and lived experience safely within a playful pop-culture format.

APA7 Reference:

- Ferguson, M. R., & Thanyodom, T. (2024). K-Pop and the creative participatory engagement of Thai fans: When cultural hybridity becomes cultural authenticity. Popular Music and Society, 47(1), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2023.2286816

Week 12

In my remix of the Memoirs of a Geisha poster, I replaced the original Hollywood-style close-up of a woman’s face with a full-body image of a geisha performing a traditional dance. Instead of floating in empty white space, the performer is positioned inside a tatami room with a patterned byōbu screen, lanterns, and layered floral motifs. This situates her within a culturally authentic environment and highlights geisha as trained artists rather than exoticised symbols.

The use of cherry blossoms, kimono textile patterns, and warm lighting creates a sense of seasonality and atmosphere that reflects Japanese aesthetics more accurately than the original. The dancing pose and fan also emphasise that geisha are performers skilled in music, dance, and hospitality — countering the Hollywood misrepresentation that reduces them to mysterious or sexualised figures. Curved lines and dynamic typography direct the viewer’s attention across the poster, creating movement that echoes the flow of the dance.

Overall, this remix critiques the decontextualisation of the original poster by restoring cultural grounding, artistic labour, and authenticity to the representation of geisha.

I use Procreate to make this Remix of the Memoirs of a Geisha poster.

Reference List:

- Pinterest. (n.d.). Geisha fan pose reference (image). Pinterest. https://au.pinterest.com/pin/779122804328046471/

- Pinterest. (n.d.). Traditional geisha kimono pattern inspiration. Pinterest. https://au.pinterest.com/pin/779122804328046504/

- Pinterest. (n.d.). Japanese floral shoji screen reference. Pinterest. https://au.pinterest.com/pin/779122804328045773/

- Pinterest. (n.d.). Vintage Japanese paper fan texture. Pinterest. https://au.pinterest.com/pin/8022105582001408/

Week 13: Cultures of the World 3

This week’s webinar invited us to experience another culture’s creative practice and to reflect on how our habitus shapes our first reactions. When encountering an unfamiliar artform, I realised that my first response often reflects shock, or sometimes a feeling of “wow, this is so beautiful or colourful”, rather than true understanding. This made me aware of how my perception is shaped by my past experiences and cultural background — what Bourdieu calls the “embodied history” that guides our tastes and instincts (Bourdieu, 1990).

The webinar also helped me see how different cultures express aesthetics and ontology through creative practices. Some cultures may use bright colours, symbolic patterns, or slow ritual actions that initially feel strange to someone outside the tradition. But as Hall (1997) reminds us, representation is never neutral — it always reflects deeper cultural meanings.

To appreciate an artform I was not raised in, I learned to ask guiding questions, such as:

-

What cultural values or worldview shape this form?

-

What does this art aim to express beyond its appearance?

-

How is meaning created through its materials, rhythm, or symbolism?

-

What worldview does this artform express?

-

What values or relationships is it trying to represent?

-

What assumptions from my own habitus are stopping me from understanding it?

By shifting from reaction to curiosity, I became more open to experiencing the artwork on its own cultural terms. This process reflects what Bennett (1993) describes as moving from ethnocentric judgement toward intercultural sensitivity, where I can recognise the limits of my own perspective and learn from another way of seeing the world.

By slowing down and engaging more openly, I found myself appreciating details I missed at first — textures, symbolism, repetition, or the rhythm of movement. This experience showed me that appreciating another culture’s creative practice requires curiosity, patience, and a willingness to suspend my automatic assumptions. My habitus does not disappear, but I can learn to notice it and create space for a more sensitive intercultural response.

APA 7 Reference List:

-

Bennett, M. J. (1993). Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In R. M. Paige (Ed.), Education for the intercultural experience (pp. 21–71). Intercultural Press.https://www.idrinstitute.org/dmis/

-

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503621749

-

Hall, S. (Ed.). (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Sage in association with the Open University.

https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/representation/book277180